The Nvidia of Batteries: A Missed Empire

In May 2025, a company called CATL, a clunky, forgettable acronym far removed from its Chinese name 宁德时代, filed for its long-anticipated Hong Kong IPO, the largest of the year. Most Silicon Valley VCs barely noticed. But inside China – and across the global EV industry – CATL’s rise is already legend. Born as ATL, a battery supplier for consumer electronics like the iPod, it has since transformed into the dominant force in the global EV cell market, commanding over 37% of global market share. Its clients include global giants like Tesla, Ford, and BMW, alongside China’s rising stars such as NIO, XPeng, and Li Auto.

CATL is now building Europe’s largest EV battery gigafactory in Hungary, with a second underway in Germany. In the U.S., Ford has partnered with CATL to bring its lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) technology stateside, according to The Information. CATL is not just supplying; it’s setting the standard of EV cell.

Just how indispensable is CATL? Think of it as the Nvidia of EV batteries. Its constant delivery delays, driven by relentless demand, have become an industry saga. In one exchange, Sequoia China’s partner Neil Shen joked with CATL founder Robin Zeng about how his EV portfolio companies could secure more supply: “More trips to Ningde (CATL’s headquarters)? Or just more baijiu with you?”, referring to the notoriously potent Chinese liquor.

And yet, Silicon Valley missed it entirely, and the upside was staggering. An early investor, Ningbo Lianchuang, cashed out billions and still held a 6.77% stake in CATL worth nearly RMB 65.7 billion (~$9B USD) as of late 2022. Meanwhile, founder Robin Zeng quietly became one of China’s wealthiest individuals, rumored to have surpassed Li Ka-shing as the richest resident of Hong Kong.

While CATL scaled quietly, Silicon Valley backed high-profile solid-state battery moonshots like QuantumScape and Sakti3 , lavished with billions in funding and media buzz, only to watch them stumble or stall before mass production.

CATL wasn’t invisible. Menlo Park just didn’t look.

To note, Sequoia China eventually joined the cap table, though the timing and scale remain unclear, and it was HongShan, post–Sequoia U.S.–China split, that made the move. The Valley at large stayed out, dismissing CATL as just another Chinese hardware play propped up by state subsidies. The irony? CATL was always in Silicon Valley’s orbit. Its predecessor, ATL, was Apple’s iPod battery supplier. ATL’s first institutional backer was a UC Berkeley and IBM alum, chairman of H&Q Asia Pacific, followed by 3i Group and Carlyle – all of whom had offices in Menlo Park, Beijing, and Hong Kong. But by the time CATL spun out and scaled, the Valley had already pivoted to SaaS, social apps, and mobile, leaving the EV battery revolution behind.

The story of CATL isn’t about one unicorn that got away; it’s a rearview mirror on how the Valley lost its hardware edge while software was eating the world. Manufacturing didn’t vanish; it evolved, and Silicon Valley VCs simply stopped paying attention. CATL broke nearly every pattern Western tech investors were trained to recognize. Doing so, they overlooked the Nvidia of EV batteries, quietly compounding through manufacturing scaling law, IP accumulation, and geo-arbitrage. More importantly, CATL now offers a blueprint for what’s being missed in today’s watershed moment: the return of global reindustrialization as the next frontier of venture capital investing.

When Software Ate the World, Manufacturing Built It.

The Great Retreat: Europe Had the Vision, But Not the Industrial Statecraft

Interestingly, Europe once dreamed of building its own battery champions. But that vision is rapidly unraveling. Northvolt, touted as Europe’s great hope, filed for Chapter 11, and 11 out of 16 European-led battery plants have now been delayed or canceled. BMW, Volkswagen, and Mercedes are scaling back, and Britishvolt never even got off the ground. As Bloomberg reports, even €55 billion in preorders couldn't keep Northvolt alive.

Europe’s battery failures, as RAND researcher Kyle Chan highlights, are largely skewed by local-led projects. Of the 13 battery initiatives in Europe led by Chinese or Korean firms, 10 remain on track. This includes CATL, LG, and Samsung; all expanding steadily while their European counterparts falter. The irony is sharp: Europe poured capital into the vision but lacked the ecosystem to deliver. Meanwhile, the very firms it sought to replace are now strengthening their grip on the continent.

Europe’s battery problems are actually skewed by European-led battery projects like Northvolt’s Germany plant.

— Kyle Chan (@kyleichan) December 10, 2024

If you look at Chinese- or Korean-led battery projects in Europe, 10 out of 13 of these are on track. And this is on top of existing plants from CATL, LG, and Samsung. pic.twitter.com/DkfEMNZCrW

How Silicon Valley Missed: the Moonshot Mirage

The year was 2011, Silicon Valley was deep in a clean energy gold rush, backing battery moonshots like A123, Sakti3, and later QuantumScape. The ambition was real, but so were the blind spots. Dozens of startups raised hundreds of millions, only to collapse in waves, leaving behind cautionary tales and political blowback. How did the Valley miss so badly? A few lessons from the misfire:.

Hardware Doesn’t Scale (Until It Does)

By the early 2010s, Silicon Valley had built a religion around software: zero marginal cost, infinite scale, minimal friction. Hardware, especially industrial hardware, was seen as slow, risky, and capital-intensive. Cleantech 1.0 flops like Solyndra, Better Place, and A123 cemented that view. Energy was too hard. Hardware didn’t scale. So capital fled to mobile, SaaS, and APIs. A new orthodoxy took hold: software eats the world, capex is death, and founders are storytellers, not industrialists.

CATL’s 2011 spinout from ATL came in the shadow of this mass retreat, right when Kleiner Perkins was sinking $75M into Solyndra’s ill-fated solar tubes. CATL wasn’t invisible; it just didn’t fit the new orthodoxy. No pitch deck, no Stanford founder, no viral metrics. Just a Fujian engineer solving battery chemistry and building real factories. Silicon Valley wasn’t looking for a battery empire. It was looking for the next Instagram.

China’s Policy Ignored, Then Proven

While the Valley were busy with app demos and burn-rate curves, something was quietly unfolding elsewhere. In 2015, China rolled out its now-famous Made in China 2025 blueprint. One of its clearest bets? EVs and battery energy density. CATL aligned with it almost instinctively. By 2020, their batteries had already hit the plan’s targets. By 2021, China owned the EV battery supply chain, and Made in China 2025 was quietly marked as mission fully accomplished. Where Silicon Valley saw policy as background noise, Chinese founders read it like a compass.

The Moonshot Mirage

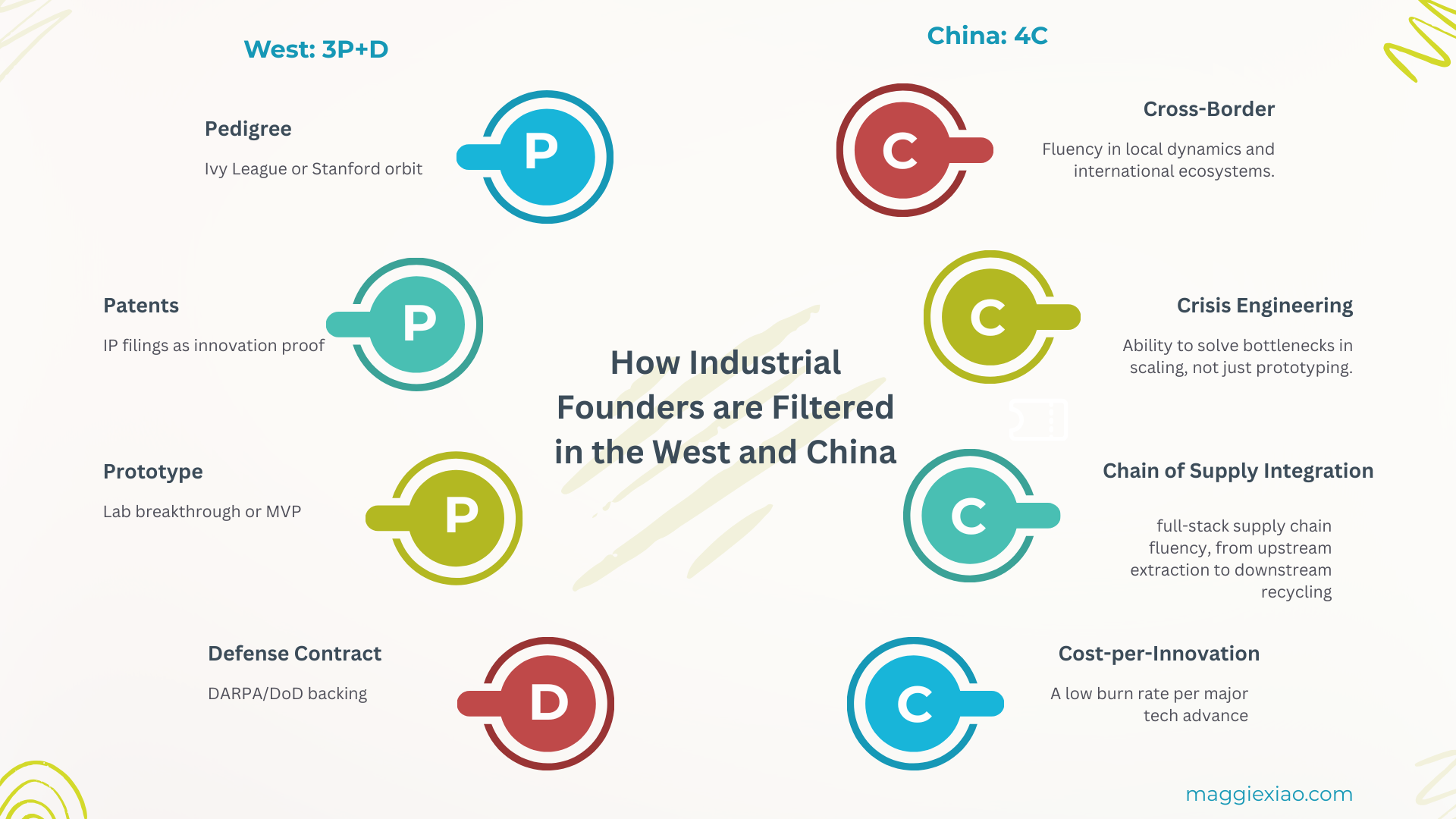

Silicon Valley didn't ignore the energy revolution; it just chased the wrong ones. In the 2010s, top firms like KPCB went all-in on clean tech moonshots. Such startups were screened through the classic 3P+D filters: Pedigree (e.g., Ivy League), Patents, Prototype, and/or Defense Contract.

QuantumScape, is a textbook of such 3P+D case: no factory, no customers, just lab breakthroughs and hockey-stick projections, determined to the moonshooting in solid-state batteries. It raised over $1B, backed by Bill Gates, promising to double energy density through solid-state chemistry. But by 2024, mass production had been pushed to 2027+, the company had lost 70% of its market cap, and shareholder lawsuits had begun.

Meanwhile, back in 2010, Robin Zeng, ready to spin out CATL from ATL, had his own moonshot: to forgo its pioneer status in consumer electronics batteries and bet on EV batteries through disciplined, incremental engineering.

Instead of betting everything on one breakthrough, it deployed a multi-path strategy: CTP (cell-to-pack) tech improved energy density by 20%; sodium-ion batteries launched in 2023 as a low-cost backup to LFP; and semi-solid-state batteries reached 500Wh/kg without full solid-state risks.

The underlying logic?

- No all-in bets. Focused on manufacturable improvements.

- Full-stack control. From mining to recycling.

- Customer-led R&D. BMW and Tesla orders shaped priorities.

The Most Misunderstood Capital: Industrial VC

If all this sounds like hindsight, that’s because it is. Hindsight makes every missed empire look obvious, but it can never reverse-engineer one. Beneath the surface of CATL’s rise lies a deeper revelation: a distinct kind of capital, Patient Industrial Capital, long-horizon, productivity-aligned, and brutally disciplined. This is the capital that fueled China’s industrial ascent, and it doesn’t fit the conventional Western VC lens.

The Myth of Subsidies

The West often reduces China’s manufacturing rise to a story of subsidies. That view isn’t just outdated; it’s misleading. The true engine of China’s industrial and long-horizon capital is more akin to venture capital at scale than blanket state support.

- State capital in China is not cheap; it’s brutally selectively

Contrary to the stereotype, Chinese manufacturing firms are not propped up by endless subsidies or easy credit. Most loans fund long-term asset formation (e.g. land, buildings, factory equipment) with high loan-to-value ratios, while operations and human capital must be funded by equity, the most expensive form of capital. This structure disciplines firms, forcing them to pursue sustainable margins rather than rely on ongoing debt to cover losses. Firms that fail to reach break-even don’t get bailed out; they get consolidated or shut down. Chinese industrial entrepreneurs either hit break-even early or die trying. No safe harbors. Just industrial Darwinism. quote tweet here

- The Chinese “state VC” model drives competition, not protection

The Chinese state often acts more like a venture capitalist than a safety net. Take the city of Hefei’s investment in NIO: it wasn’t a bailout, but an equity injection at the company’s lowest valuation: high risk, high reward. The local government later exited with a large profit, making headlines as 'China’s VC of the Year is a City.' The episode reveals how state capital can be both strategic and return-seeking, not protectionist.

- Industrial Darwinism, not bloat

Tens of thousands of uncompetitive industrial firms are eliminated or consolidated every year in China. CATL and BYD didn’t rise because of state favoritism, but because they survived and outperformed in an environment where only the most efficient operators win. This reality contradicts the Western narrative of a 'bloated' or 'subsidized' industrial base. China’s industrial financing system is designed to support capital-efficient, export-capable firms, not to keep zombie companies alive. And that makes it one of the most misunderstood forces in understanding state capitalism

Equity Financing Aversion: How Industrial Founders Think about Capex

A stark contrast to the equity-heavy financing model of Western EV startups is how advanced manufacturers like CATL and BYD actively avoid equity dilution.

As entrepreneur and former PE analyst Glenn Luk points out, in China, factories and infrastructure are funded with collateralized bank loans, often up to 80% loan-to-value, and channeled through state-aligned banking systems. Speculative projections don’t matter but physical assets do. But what about daily operation and R&D? Those still require cash flow or equity injection, forcing firms to prioritize profitability from day one.

Typical industrial or manufacturing companies are a mixture of:

— Glenn (@GlennLuk) August 10, 2024

(i) long-term assets e.g. land & buildings

(ii) medium-term assets like factory equipment and

(iii) operations / human capital.

This model diverges sharply from Europe’s approach. Startups like Northvolt raised billions in equity just to get off the ground, diluting founders and leaving fragile cap tables. In China, those same needs are met through structured debt and disciplined growth. Firms that can’t make it work don’t get another chance. BYD, for instance, has more cash than debt on its balance sheet and achieved a 14.5% return on equity in 2022.

That leads to another key distinction from Western industrial entrepreneurs: in China, ownership stays with the manufacturing founders. As of CATL’s 2025 IPO filing, founder Robin Zeng held 26.39% of the company, while his early team, Huang Shilin, Pei Zhenhua, and Li Ping, retained another 24.6%. That’s over 50% in the hands of founders, almost unheard of in the West where industrial founders are often diluted long before scale. This is what productivity-aligned capital looks like: strategic credit matched to real assets and long-game execution, without trading ownership for narrative.

The Paradox of CATL is the Next Opening for Western VCs

CATL’s Valuation Paradox

However, the aversion to equity financing has its drawbacks. Despite leading the largest IPO of 2025, CATL’s valuation remains surprisingly modest. As of June 2025, Tesla trades at a sky-high P/E ratio of ~165×, Nvidia at ~46×, while CATL lags far behind at just ~21×, despite being the global EV battery leader. CATL trades at a significant discount.

That’s CATL’s paradox: it leads the market but doesn’t get priced in. It builds quietly, and the market stays quiet too.

As described earlier, in China, founders like Robin Zeng have long avoided equity financing, not just for control, but due to a uniquely Chinese phenomenon: 内卷 (involution). In this hyper-competitive environment, capital isn’t always empowering; it can be corrosive. The influx of funding into verticals often leads to diminishing returns and gives competitors the chance to replicate, escalate, and erode margins. As a result, industrial entrepreneurs like Zeng optimize for profitability and resilience over valuations.

But that mindset, forged in domestic competition, becomes a constraint on the global stage. Robin Zeng are starting to recognize the shift. His next frontier is energy storage and global grid infrastructure, an arena that requires more than engineering, it demands capital visibility. On the global stage, the logic flips: equity isn’t just dilution, it’s an amplifier. It brings reach, legitimacy, and valuation leverage. Western startups often enjoy this reflexively, Chinese firms, constrained by geopolitical headwinds and domestic financing norms, rarely do. CATL’s muted valuation says less about its fundamentals, and more about its capital logic.

CATL’s Vision Map Needs Global Capital

Equity, deployed strategically, can unlock the kind of scale that internal cash flow alone can’t sustain, especially when the window to move is now. Once that realization sets in, CATL’s decision to dual-list in Hong Kong starts to make sense. For a founder historically cautious about equity injection, it signals a shift.

Zeng’s vision extends beyond EV batteries. In his own words:

“以可再生能源为核心,替代传统的煤炭、石油、天然气的化石能源;以动力电池为核心,替代传统的加油、加气的移动式化学能源;以电动化 + 智能化为核心,实现市场应用的集成创新。”

The phrasing, with its formal cadence of Chinese industrial speak, may sound generic at first. But here’s the real translation: CATL isn’t just building batteries anymore. It’s positioning to lead the next energy paradigm, entering the global arena of energy storage and electrification-as-a-service, just as grid intelligence becomes the new infrastructure battleground.

That's why industry insiders see CATL's 2025 dual listing as more than a liquidity event, but a pivot into a platform orchestrator. And this time, Western capital may not just be welcome, it may be essential.

The New Industrial Playbook: a Field Guide for Western VCs

We’re entering a new era of re-industrialization, and the EV revolution is just the beginning. Robin Zeng’s CATL points to what’s next: a global remapping of the energy stack, infrastructure, and power systems. For Silicon Valley, the door isn’t closed, but it requires a new mindset. The next CATLs won’t come from demo days, but from industrial clusters and geopolitical fault lines. To find them, VCs need a new playbook.

Go Where Energy or Commodity is Cheap

Europe’s battery failures weren’t just about funding; they were about cost structure too. In Germany, high energy prices made manufacturing unviable. Ironically, China, still an energy net importer, didn’t wait for perfect green transition. Instead, it launched an industrial-scale, all-of-the-above energy reform: updating state grids anchored by fossil, hydro, solar, wind, and nuclear. Instead of scarcity, the result was abundance, even oversupply, in electricity.

The logic extends to materials. By 2011, China already controlled 90% of global rare earth separation capacity, a fact largely ignored by Western VCs during the clean tech investment frenzy.

The lesson for U.S. investors is clear: this isn’t just about backing founders, but securing input control. On a 1970s grid, factory dreams die in the cradle. Energy and industrial startup buildings must go hand-in-hand with state-level grid reform.

Bet on the Quiet (but Best) Operators

One thing in common among entrepreneurs like CATL’s Robin Zeng and BYD’s Wang Chuanfu: they are quiet.

In conversations with Elon Musk, Zeng dismissed Tesla’s 4680 battery design outright: “It’s going to fail. It’s electrochemistry.” Musk, usually unfazed, reportedly went silent. Zeng also questioned Musk’s habit of setting aggressive, unrealistic timelines, viewing them as distractions from disciplined execution.

Pretty interesting comments on Elon Musk and Tesla's battery efforts by Robin Zeng, the founder of China's CATL (the world's largest battery company by far, and Tesla's foremost battery supplier): https://t.co/FeZYn4pXgg

— Arnaud Bertrand (@RnaudBertrand) November 17, 2024

He speaks with Musk often and said he told him directly…

Reportedly, Zeng called the 6% EV penetration rate as the tipping point and framed it as a do-or-die threshold. By the time the 6% mark arrived in 2021, CATL was already the leader.

Speaking of 'paranoia always wins,' Zeng bet on both sides of the battery chemistry debate: LFP and ternary, because uncertainty demanded strategic hedging, not narrative-riding. He even banned PR teams from using the phrase 'world’s number one,' preferring instead 'temporarily leading in shipments.'

While Western VCs use 3P+D as a filter, where entrepreneurs like Zeng don’t fit, they are welcomed, and often fiercely competed for, by China’s industrial-minded local governments. These 'tech repats' are known for their 4C credentials: cross-border expertise, crisis engineering, chain of supply integration, and a cost-per-innovation mindset.

These quiet operators rarely show up on pitch decks. But they’re exactly what industrial alpha is made of.

The Winner Takes Two

The G2 framework may have failed as a political idea, but it endures as economic structure. The U.S. and China are now dual gravity wells: fractured in ideology, fused in supply chains, tech stacks, and capital flows.

The winners? They take both. Tesla’s 4680 design fused with CATL’s CTP manufacturing now commands 60% of the global EV battery market. This isn’t decoupling; it’s winner-takes-both.

Backing companies like this – hybrid by design – is the edge. The VCs who win this era will be bilingual in tech and geopolitics, reading soft signals from Beijing and D.C. as fluently as they read a term sheet.

Technology is no longer politically neutral. Global swing states are now a tech industry mindset. From Seattle to Shenzhen, the next breakout firms won’t rise despite geopolitics, but because of it.

Global South Playbook: Industrial Equity in Multipolar Order

As the post-dollar era unfolds, VCs are entering what could be called Emerging Markets 2.0. This cycle isn’t about chasing commodity booms or riding dollar-based asset inflation. It’s about reindustrialization in a multipolar industrial era.

In this shift, the Global South is no longer a dumping ground for overcapacity. Southeast Asia, MENA, and Latin America aren’t just cheap labor pools or export targets anymore, but undercapitalized potential. What’s missing isn’t talent or demand, but capital aligned with infrastructure, localized production, and long-horizon market logic.

The new industrial leverage equation is simple:

Technology Output × Local Capacity = Political Hedge + Cost Reset.

In other words, tech exports alone won’t cut it. One need plants on the ground.

This is a different playbook from last industrialization: not won by IP hoarding or offshore licensing, but through manufacturing-led R&D and embedded supply chain. The same year QuantumScape went public with no product, CATL’s German gigafactory broke ground .

CATL’s pivot offers a model: no longer just a battery maker, it’s positioning itself as a platform player: spanning energy storage, grid intelligence, and electrification-as-a-service. To scale that vision globally, equity isn’t optional. It’s the unlock.

In this kind of geo-arbitrage world, equity isn’t hype fuel; it underwrites industrial ambition. Industrial investors who bring not just capital but deep understanding of market terrain, regulatory texture, and geopolitical logic will become co-authors of the next global order.

DeepSeek in Energy, Scaling Law in Manufacturing

In Silicon Valley, capital efficiency used to mean “light and fast.” Scale was software. Moats were patents. And capex-heavy businesses, like battery factories or upstream supply chains, were filed away as unscalable, unsexy, and unfit for venture capital. But in the new reindustrialization era, that logic is breaking.

While U.S. battery startups raised $2.8 billion in 2023 with a few made into global stage , CATL quietly scaled a global moat, not through IP monopoly, but through supply chain control and manufacturing scale. It owns lithium, cobalt, and nickel reserves across the Congo and Indonesia. It builds full-stack “lighthouse factories” in China and Germany with 47% higher efficiency than their American counterparts. Each $1 of CATL capex generates 2.3× more patent output than U.S. peers, on par with DARPA’s budget-to-GDP ratio, but with five times faster commercialization.while Western founders chase grants and suppliers, CATL engineers down the learning curve: faster, deeper, cheaper.

And it wasn’t just theory. In 2011, Apple paid $8 per battery cell to ATL (CATL’s predecessor) while Fisker paid $43 per cell to U.S.-based A123. A decade later, CATL’s LFP cost reached $97/kWh, beating the U.S. average of $128/kWh.That's the industrial scaling law at play.

When software ate the world, manufacturing built it. When SPAC’d apps went boom and bust, industrial-scale tech companies like CATL were building heavy assets, not fixed costs, but defensible moats.

The takeaway ? Industrial venture capital needs a new playbook. Moats won’t just be patents but a new scaling law of advanced global manufacturing. They’ll be multi-decade capex curves backed by geopolitically aware equity. It's time for Silicon Valley VCs look for DeepSeek in energy , in hardware; it’s time to stop dismissing capital-intensive industries, and start underwriting them like the future depends on it.